On Assisted Dying

Why (despite years of being pro) I've decided the 'easy' route out is not for me...

I have been very pro-Assisted Dying since early 2019, when my cancer-riddled father started trying to persuade Dignitas (which he’d joined) to let him off-himself, asap.

An 82 year-old single gentleman of implacable obstinacy at the best of times, he was now—during the worst of times—in no place to be persuaded otherwise. Unfortunately, he’d also left it too late; unable to travel without assistance he couldn’t persuade anybody, least of all me, to accompany him.

My Pa had refused further treatment for his bladder cancer in late 2017; I was with him at the appointment where he proudly declared he’d ‘had enough of all this nonsense’, at which point his (female) consultant called him ‘nihilistic’. I told her I thought that was a bit much when my father took a lavatory break midway through the appointment. She was a woman of my age and simply grinned: ‘He’s a handful, right? Reminds me of my father, actually.’

Well, yes, my father was ‘a handful’. And he did nothing to make (what turned out to be) the last six months of his life any less stressful by deciding in January 2019 to start taking occasional fake ‘overdoses’ of Paracetamol (after texting lengthy and dramatic GOODBYEs to friends and family).

My father was not a brave man. I knew he had no intention of committing suicide so messily—much less alone; his behaviour was the proverbial ‘cry for help’. However, if the ‘help’ — ie legal assisted dying for somebody in the final months of their life — had been available I do think he would have taken it. I have no doubt that he’d genuinely had enough and was as ‘ready’ to go as any of will be — having been fit and healthy well into old age the lack of dignity and personal compromises were now too great to sustain the independent life he was used to. However, it was his inability to make that happen on his own terms — plus his rapidly deteriorating mental health — that ensured the last few months of his life were a very difficult period not only for him, but for me (his only child) and a few of his closest friends.

He became all but impossible to be around—endlessly manipulative in his dying rage. Eventually I was forced to call his bluff, telling his (fantastic) GP he was constantly threatening suicide, which also meant I couldn’t let my sons (whom he adored and who were then 12 and 16) anywhere near him. Which in turn had added to his distress and the sense he was being ganged-up upon… which he inevitably turned back on me. After I blew the whistle he came close to being sectioned for his own safety but managed to wriggle out of it by being persuasively compos mentis when the necessary doctors swung by his hospital bedside to assess him.

There was no space in a nearby hospice and Dad was only prepared to go to one (ferociously expensive, this being Notting Hill—though he could afford it) local care home. Having got the lowdown on his behaviour they came to assess him at home, only to be confronted by such an angry and difficult man that, unsurprisingly, they rejected his application.

When Dad finally conceded that somebody needed to look after him — having refused external carers entry to his flat — he spent just one night in a ‘horrible fucking place full of fat, stupid nurses’ before phoning a friend and demanding to be sprung. Just a couple of weeks later, having been discovered by that same friend lying on his flat’s communal landing he was taken to Chelsea and Westminster Hospital—where he stayed (and was looked after beautifully) for the final week of his life.

I had been with him the evening before he died and was in the shower, preparing to go back for another bedside shift, when I missed a 7.30am call from the hospital. I phoned back — to be told he’d gone: ‘But you’ve no need to worry, he wasn’t alone’ said the nurse, kindly. Yet I wasn’t remotely worried. I knew—immediately, instinctively—that he had been alone, and that not only would he have been fine with that but (despite being unconscious) he’d probably orchestrated it during the staff’s morning shift change. He was also an Only Child—and we like our space.

2019 was a very stressful year. I lost a friend, quickly, from cancer that autumn and then we segued into 2020 and the chaos of Covid. I said goodbye to my mother on the phone a few days before she died in October of that year (she lived in Australia, where the borders were shut). While I do not know, in truth, if I would have travelled to her bedside to say ‘goodbye’ it would have been nice to have had the choice. She did not die alone, however — she had my sixteen years younger half-brother with her. (He was raised as an Only Child, too—it’s complicated).

Anyway, after my mother died I attempted to draw a line under all that death. Until my 21 year old eldest son died in an accident in September 2023—and that changed everything.

You don’t need to ‘make sense’ of the death of an octogenarian. Or rather, I don’t. Unsurprisingly, however, I do need to make some sort of ‘sense’ of my son’s death. It will remain the work of whatever is left of my lifetime.

One outcome, however, has been a shift away from my previously incontrovertible support for Assisted Dying. I’d often joked to my sons about ‘putting a pillow over my face’ if I had dementia; plenty of us make similar jokes behind closed doors. However, my previously blackly comedic vision of my robustly healthy sons fighting for the privilege of suffocating their ga-ga mother collapsed entirely when I knew only one of my children would be shouldering the burden.

Having been an Only (and I discovered I was no longer going to be one at the age of 16, when confronted by my heavily pregnant mother on the other side of the Arrivals gate at Canberra airport in December 1980; long story), it was never my intention to have just one child. Managing decaying parent/s and dealing with death’s inevitable ‘sadmin’ can be exceptionally onerous. I am of course now very sad that my youngest son has to bear some of this in his future, alone—even though I will do (nearly) everything I can to make it less painful for him. And I say ‘nearly’ because that no longer includes an Assisted Death.

One of the many things I have asked myself over the 14 months since Jackson’s death is: What was the point of him? What was he for?

I put a lot of energy into birthing and raising him—as most mothers do—and just as he was at the end of his post-graduation summer-of-fun, on the very threshold of what (one hoped) would be an interesting and rewarding adult life, he walked out of the house on an ordinary Tuesday evening in late September... and never came home.

He was dead — and with that his future was now also denied to those of us left behind. So, what was the point of him?

If I have any ‘belief system’ at the age of 60, it feels far closer to that of the ‘Only’ kid who took herself off to Sunday school voluntarily (it was a very handsome church and I like hymns), which in turn segued into reading about comparative religion and wanting (and failing) to understand physics—settling in my teens for understanding at least some of Fritjof Capra’s ‘The Tao of Physics’, before eventually embarking on a Philosophy and Theology degree at King’s in my early twenties. (After a stint as fashion and features editor of The Face; I never felt any friction between an abiding interest in shoes and wanting to understand the meaning of life).

Look, I know what the ‘point’ of my son was... for me. Being a parent, twice, has made me a better person than I would have been had I not become a parent. Which is not to say — before somebody says it for me — that child-free people do not also become ‘better’ people; they just do it via a different algorithm. For me, though, having children was an essential part of the narrative. By turns terrifying/enervating/tedious/ thrilling and hilarious, I am whatever it is I am now largely because of what raising my children has taught me—not least about myself.

Nonetheless… what was the point of Jackson... for Jackson?

I have asked several people who work around/with/after death this question and they have all said effectively the same thing: that the answer is beyond our collective — ie humanity’s— pay grade. Some of those with a belief system have also suggested that I ‘wait and see?’

And that is exactly what I will do for the rest of my days—wait. Not passively—I have plenty of stuff I want to do in the meantime—but very much with the sense I now have of existing in a liminal space, in animated suspension between my old life as a working mother of two living sons… and where I am now: a place where one son is living and the other is dead, yet also ‘exists’ (perhaps) somewhere in the space-time continuum, at a quantum level, as energy. (Incidentally, Jackson’s ashes are contained about ten feet away from where I’m typing this, though they are rarely the focus of my attention).

Since Jackson’s death my position on Assisted Dying has shifted. I still think it should become Law—yet as my son’s Physics degree butts-up against my abiding interest in Philosophy and Theology I find I’m having ‘conversations’ with him— internalising debates that would, in my old life, have played out physically, over time. We were having so many fascinating conversations shortly before he died; I miss them/him so much.

Having seen one of my old life’s ‘certainties’ — that my sons would outlive me by many years — turned to ashes, I don’t now think I will be availing myself of the neat ‘certainty’ of Assisted Dying’s tidy, box-ticked, medical-industrial-complex collision with consumerism. I remain ‘pro- choice’ for you—just not so much for me.

I guess that’s easy to say from where I currently sit. Yet, just as I couldn’t/didn’t (to my ‘knowledge’) actively ‘choose’ the manner and time of my birth, I now feel the context of my death is also beyond my pay-grade. However tough it may be for me to take, I currently believe that death (like birth) should — a tricky word in itself, because who/what ‘decides’?— probably be whatever it will be.

I feel fatalistic about my own death because I feel my son was ‘taken’ and I need to make sense of the ‘why’. And though I appreciate intellectually that there may be no ‘why’, accepting that as a capital-T Truth doesn’t work for me. It is precisely because my son didn’t stay around long enough to fulfil his potential — nor get to choose the time of his departure — that I now feel I owe it to him to go my own life’s distance, in all its messy, ineffable, mysterious (if not mystical) entirety.

At which point (because why not? I am not the Boss of this stuff!) maybe I’ll find Jackson waiting, smiling that (incandescent, head-turning) smile and reaching out for a hug: ‘See, Mum, that wasn’t so bad—was it?’

Yeah, I think that would be worth waiting for…

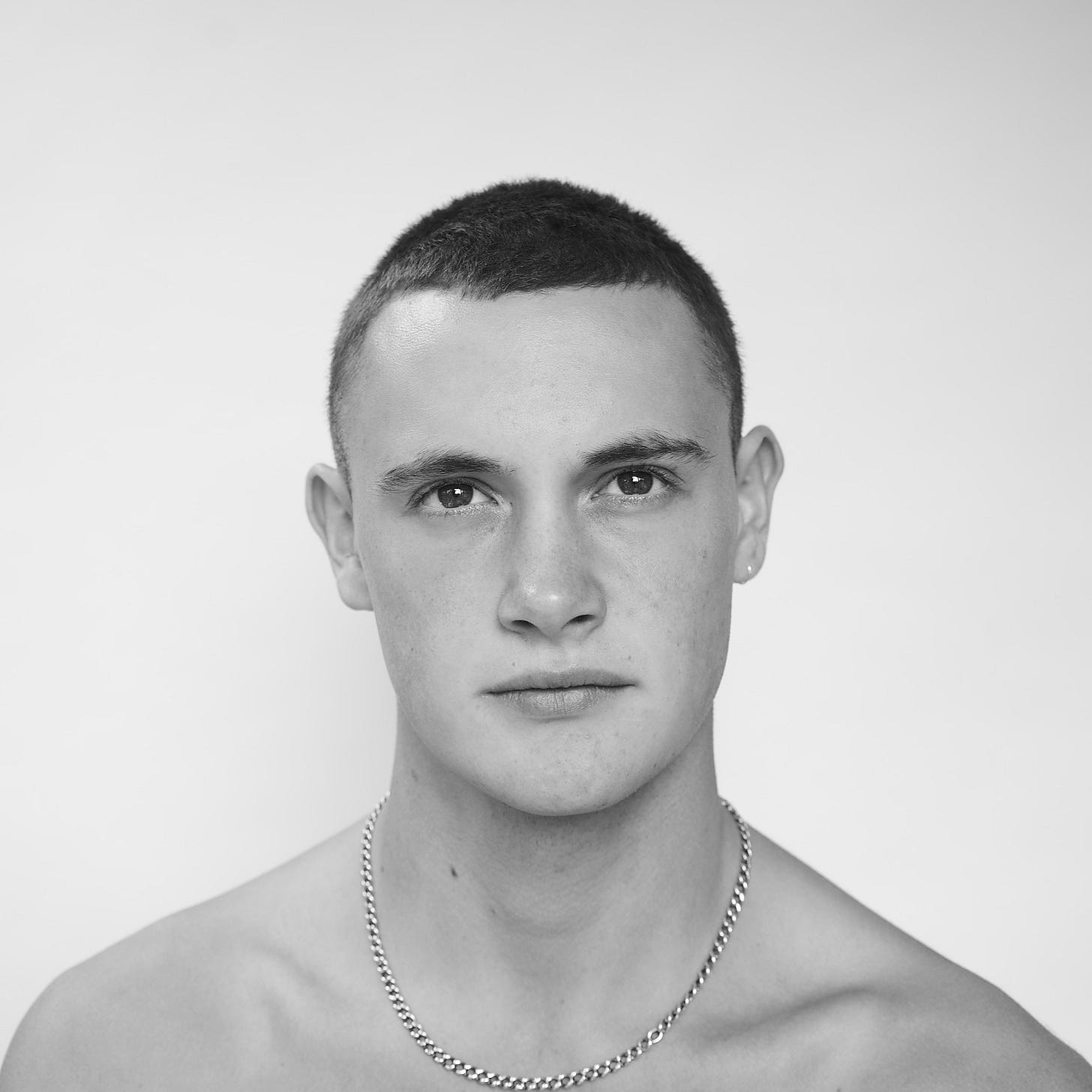

Portrait of Jackson Peacock by my partner JULIAN ANDERSON

Because I choose to write here so irregularly I still don’t feel able to charge for my Substack. However if you like what I write please do feel free to support my work and BUY ME A COFFEE!

Love and thanks, Kate x

What a thoughtful, moving piece, Kathryn. No wonder Jackson's death has made you reassess.

My own views on assisted dying shift – and keep shifting. I think of my previously fit and active aunt who had a devastating stroke in her eighties which left her unable to move or speak. She could still understand me, and I knew there were times when she wished she could finish it, not be left in this locked-in state. She lived for another two years and in the end simply stopped eating. But if assisted dying had been available, I don't know when that would have been appropriate or who would have made the decision.

My mother was in tremendous pain before she died and went through a phase of pleading with the nurses to give her enough morphine to kill her. But then the pain receded and she was in a much calmer and more accepting state of what will be, will be.

"What is the point?" is a good question. I asked myself that, after I had stillborn baby at full-term in 2000. I remember a dream where I took my place in a line of women who had lost babies and children that stretched back through all of humanity, and it stretched forward, too. It didn't answer my question but it helped me feel less alone.

Thanks for writing this heartfelt piece.

It's a beautiful picture of Jackson. I'm glad you're still able to continue your conversations with him in your own thoughts.

Extraordinarily beautiful post xxx